The Crusade against the Cathars

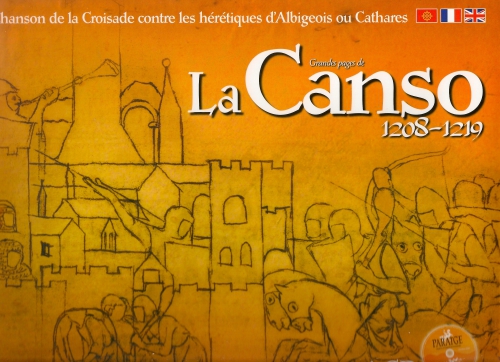

La Canso

I have just purchased this splendid book, which tells us the tale of the Crusade against the Cathars from 1208 to 1219.

“La Canso,” this superb modern edition, is taken from the medieval document, bound as a book, and written in Occitan. Christian Salès, of Group Oc, wrote and published “La Canso” with the help of Anne Brenon, a Cathar scholar renowned throughout France, and various translators.

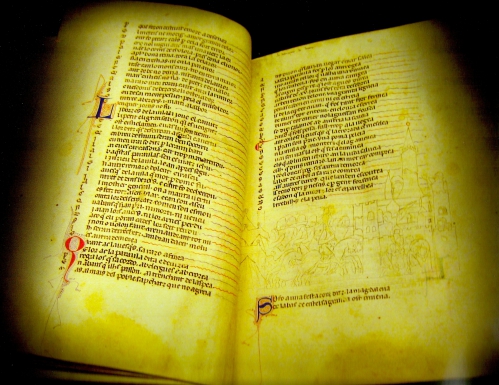

La Canso - the original - tells the story of the Cathars during the early part of their persecution. It is in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris; the picture shows it opened at the page about the massacre of the Cathars at Béziers. It was written by Guilhem de Tudèle.

Guilhem was a priest in the service of Baudouin and the half-brother of Raymond VI, brought up in Paris where he “passed into the party of the French.” He was made a canon of St. Antonin de Rouergue when Simon de Montmort took the town in 1212. Guilhem’s manuscript ended after the preliminaries to the battle of Muret, implying that the falling apart of the French party in Occitania had rendered his enterprise in vain. Guilhem was Catholic and pro-French so was naturally hostile to Toulouse, even though he did not approve of the excesses of the crusade. Remember, this was before the Inquisition, and before the death of Simon de Montfort at Toulouse in 1218.

The poem itself, from a literary point of view, was in the style of the Chanson d’Antioche, written around 1130, and had every other line rhyming. It’s artistry is stunning.

Christian’s edition of la Canso contains extracts from the original poem in Occitan, in French AND in English. It is an excellent work from 800 years ago. It is original. So here’s some extracts;

The Call to the Crusade, 1208 to 1209

Of course you all know how the heresy - God send his curse on it! - became so strong that it gained control of the whole of the Albigeois, of the Carcassès and the Lauragais. All the way from Bordeaux to Béziers most people believed in it and supported it! When the Lord Pope and the other clergy saw this lunacy spreading so much faster than before and tightening its grip every day they sent out preachers. The Cistercian order led the campaign and time and time again sent out its own men. A meeting was held at Carassonne with the Kings of France and of Aragon and others with the Bulgars at Carcassonne. Once he heard the details of this heresy, the King of France retired and sent a letter to Rome.

What shall I say? They think more of a rotten apple than they do of sermons, and went on just the same for about five years. These lost fools refused to repent, so that many were killed, many perished, and still more will die before the fighting ends. It cannot be otherwise. Once they knew their sins would be forgiven, many took the cross in France. Never have I seen such a gathering as they made against the heretics and clog-wearers!

The “Example Made” at Béziers

A pardon was offered and so an army came flocking to Béziers. The idea was to take Béziers, Carcassonne, Toulouse and Albi.

Day and night Raymond Roger, the Viscount of Béziers worked to defend his lands, for he was a man of great courage. Nowhere in the whole world is there a better knight or one more generous and open-handed, more courteous or better-bred. He was Count Raymond’s nephew, his mother was the Count’s sister. And he was certainly Catholic; I call to witness many a cleric and many a canon in their cloisters. But he was very young and very friendly with everyone, and his vassals were not at all afraid or in awe of him but laughed and joked with him as they would with any comrade. And all his knights maintained the heretics in their towers and castles and so they caused their own ruin and shameful deaths. The Viscount himself died in great anguish, a sad and sorry loss, because of his great error . . .

Raymond had to return to Carcassonne and the Jews of Béziers went with him. The Bishop of Béziers begged the people to recant.

But the majority of the townspeople said they would rather be drowned than take his advice, that the crusaders should not get as much as a pennyworth of their possessions or in any way change their rule over the town.

(From this it is clear that it was not just a religious war, but that the French army would take the town and the goods of the people. It was an out-and-out aggressive act. Simon de Montfort had been instructed to take the towns for the King of France.)

The Lords from France and Paris had all agreed that at every castle the army approached, a garrison that refused to surrender should be slaughtered wholesale, once the castle had been taken by storm. They would then meet with no resistance anywhere, as men would be so terrified by what had already happened. . . . That is why they massacred them all at Béziers, killing them all. It was the worst that they could do to them. And they killed everyone who fled into the church, no cross or altar or crucifix could save them. They killed the clergy too, and the women and their children.

The fall of Carcassonne 1209

Out they came, citizens, knights, noblewomen and girls, each running as in a race, till there was no one left in the town, no sergeants or boys, no women, no youngsters, no men, great or small. Quite unprotected, they rushed out pellmell in their shirts and breeches, nothing else; not even the value of a button were they allowed to take with them. This way and that they scattered, some to Toulouse, some to Aragon, others to Spain, and the crusading army entered freely into the citadel and occupied the hall, the towers and the keep. They piled all their fine booty into a heap and shared out many mules and horses as they thought best.

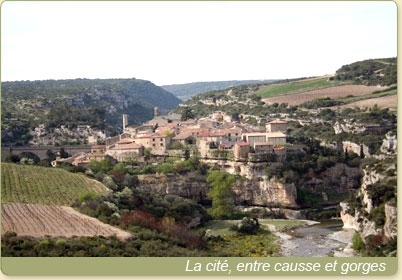

Have you nerves of steel to read what happened at Minerve?

Against the host of Christ, the judge of all, no high rocks, no steepness may avail, no mountain fortress hold out. Minerve castle is not on a plain but stands, God be my witness, on a high spur of rock. There is no stronger fortress this side of the Spanish passes. . . William, Lord of Minerve, had shut himself into the castle with his whole troop and was taking his ease there. But our Frenchmen drove them all out by force before the grain ripened. And there they burned many heretics, frantic men of an evil kind and crazy women who shrieked among the flames. Not the value of a chestnut was left to them. Afterwards their bodies were thrown out and mud shovelled over them so that no stench from these foul things should annoy our foreign forces.

(In my book, The Mayor That Was Me, I explain the dread I used to feel taking holiday-makers to Minerve, long before I got interested in local history here.)

The destiny of Lavaur May 1211

I think the horror of it all was getting to Guilhem de Tulède by this time. . . he repeats himself.

Lavaur is a strong town . . . There were many knights inside including Sir Aimery, brother of Lady Girauda, who was the lady of Lavaur. Sir Aimery joined her there after he had left the count of Montfort without a word of farewell. He had lost Montréal, Laurac and all his other lands to the crusaders, they had reduced his fief by two hundred knights and he was angry. . . alas, the day he met the heretics and the clog-wearers! Never has so great a Lord been hanged in all Christendom, nor with so many knights by his side, more than eighty . . they collected four hundred of the townspeople into a field and burned them. Beside this, they threw Lady Girauda into a well and heaped stones on top of her, which was a sorrow, for no-one in this world ever left her presence without having eaten. This was done on Holy Cross day in May. Then there was so great a killing I believe it will be talked of to the end of the world . . . it is right they should be punished and suffer so terribly for they refuse . . .to obey the clerics and the crusadors, they will not do as they are commanded . . . they will find no grace in the world or with God. There they burned at least four hundred evil heretics, heaping them all onto one great funeral pyre. . . . Sir Aimery was hanged . . . Lady Girauda was taken, and she shrieked and screamed and shouted. They held her across a well and dropped her into it and threw stones on top of her.

And so the story continued. I find it difficult to write about this horror, and I can see that Guilhem was starting to find it difficult too. And so I can only continue to Toulouse in 1218.

The Death of Montfort June 1218

The Count shook and sighed, his face black with grief. “Jesus Christ the Righteous, give me death on the field or victory!” He ordered his men to assemble . . . Their shouts, trumpets, horns and war cries, death flying from the slings and stones clattering from the mangoels came like a snowstorm, like thunder and tempest, and shook the town, the river and the riverbank. . . . the men made a sally across the orchards and the gardens, and sargeants and javelin-men filled the area. Slender arrows, round stones and fast strong blows came flashing like flame from either side,l ike wind and rain, like a rushing torrent. Now from the left-hand parapet an archer let fly and his bolt hit Count Guy’s horse on the head and drove half its length into his brain. As the horse turned, another crossbowman with a bow fully wound and ready shot at Sir Guy from the side and struck him on the left side of the groin, leaving the steel deep in his flesh; his side and breeches were red with blood. Guy rode up to his brother, his good friend, dismounted and said as a devil might; ”Brother, God has thrown me and my comrades to the ground, it’s the robbers he’s helping. This wound will make me a Hospitallier!” As Sir Guy was starting to speak and yell, there was in the town a mangonel built by a carpenter and dragged with its platform from St. Sernin. This was worked by a noblewoman, by little girls and men’s wives, and now a stone arrived just where it was needed and struck Count Simon on his steel helmet, shattering his eyes, brains, back teeth, forehead and jaws. Bleeding and black, the Count fell dead to the ground. . . .

The French went away, leaving a great deal behind them, many dead and slaughtered, including their Count, who had ceased to exist. . . . straight to Carcassonne they carried his body and buried it with offerings and masses in the church of St. Nazaire. The epitaph says, for those who can read it, that he is a saint and martyr, who shall breathe again, who shall wear a crown and be seated in the kingdom. And I have heard it said that this must be so, if by killing men and shedding blood, by damning souls and causing deaths, by trusting evil counsels. by setting fires, by destroying men, dishonouring paratge, seizing lands and encouraging pride, by kindling evil and quenching good, by killing women and slaughtering children, a man can in this world win Jesus Christ, certainly Count Simon wears a crown and shines in heaven above.

Guilhem’s pain shines through his words. He was a great writer. This is no doubt a contemporary account, written as it happens.

I have just given you a glimpse here. The Book “La Canso” by Christian Salès is available by clicking here.

Do you know the Catholic Church tried to make Simon de Montfort a saint for his “services to Christianity?” The outcry was such they let the matter drop.

Inscrivez-vous au blog

Soyez prévenu par email des prochaines mises à jour

Rejoignez les 28 autres membres