REINCARNATION - the Celts

Reincarnation, Celtic Style  Eternity - the lines never end

Eternity - the lines never end

The Celts believed in the “transmigration of souls.” This was so deep within them that St. Patrick, the Celtic Christian saint who traveled to Provence, never lost his belief in reincarnation, in the eternal life of the soul that could return.

The Celts, in their various tribes, lived throughout Europe. They were linked not by physical appearance nor by genetics, but by the common language and common beliefs.

Here’s a quote; The Celt himself did not create any great architectural work of literature. His thinking and feeling were esentially lyrical and concrete. Each aspect of life impressed him vividly and profoundly. He was sensitive and impressionable. He had little gift for the establishments of institutions, capable of being fossilised into barren formulae, thus fettering instead of inspiring the soul. The Celt has done an infinite service to the world by insisting that the true fruit of life is a spiritual reality, never to be obscured amid the vast mechanism of material civilisation.

That is so profound.

The earliest evidence of Celtic beliefs, from Megalithic days, were dolmens. There are literally thousands in Languedoc, consisting of upright stones, with a single huge stone making the roof.

The Dolmen de las Fadas (Occitan for the Fairies' Dolmen) at Pepieux in the Minervois

These dolmens were the houses of the dead. Sometimes they had a stone porch to one side, leading to the interior. Sometimes they faced east or south so the sun shone on the inhabitants. Don’t confuse them with cromlechs, a circle of standing stones - sometimes with a dolmen in the centre, the grave of a cheiftain perhaps? Dolmens were sometimes covered in earth or stones, to make a mound like Newgrange in Ireland. Some have been excavated and iron objects have been found; the Megalithic Age turned into the Iron age around 500BC.

Cairn in Brittany

Meanwhile, the Greeks and Romans, also originally Celtic tribes, were becoming great thinkers and philosophers. Michael Baigent (author of The Jesus Papers) tells us the story of Parmenides, who was important because he had traveled to the Far World - and returned. Parmenides wrote that his visit to the world of the dead brought him great wisdom. He could only do this by dying before he died and he makes it clear that the “Far World” was his home.

In 1879 an Italian archeologist examined some graves dated 444BC. Two contained thin gold plates by the body of the dead person, tightly folded; when unrolled it was revealed that these messages were to help the dead person on his way to the Far World. Baigent interprets this as Egyptian in origin. Another advises the traveller to the Far World to say, when questioned; I am a child of earth and starry heaven, but my race is of Heaven alone. It became evident to Baigent that initiations were performed to enable people to travel to the Far World. He also has evidence that Jesus Christ himself studied these practices in Egypt.

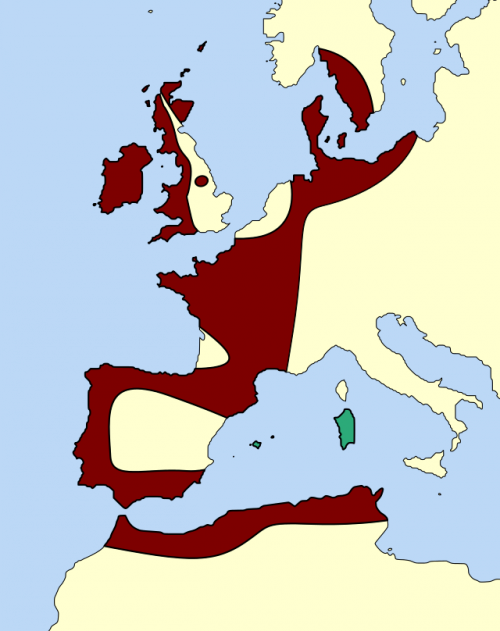

You can see how the ancestors of the Celts spread over Europe

You can see how the ancestors of the Celts spread over Europe

The Megalithic people moved from Spain through the Pyrenees to Languedoc about this time, from there spreading to all of Europe. The Romans called them the Galatae. Caesar identified the three Celtic peoples of Gaul as Belgae, Celtae and Aquitani, the last being the people of the south-west, the area from the Garonne estuary to the Mediterranean. The Aquitani were Iberian, hence the typical brown-haired, brown-eyed and not very tall people, native to Languedoc.

Their dead were not burned but buried whole, often with their possessions; like the Egyptians, the people believed the dead would one day come back. To the Egyptians also, the Far World was not seen as separate, but ever present, existing simultaneously with the physical world, inextricably intertwined with it, eternal in that it was outside time. The Celts believed the same. The Far World existed where the sun set - in the west, the Egyptians said. The Celts of Brittany also said the Far world existed across the sea to the west, and sometimes people would go there for six months and return. (But as they always returned in the spring, this is now thought to have been a parable of the deadness of the earth through the winter months.)

The Celts were very impressed by symbols from the natural world; a bird’s flight could be devined to be a message and three eagles was very powerful indeed. They loved animals in a totemic way, such as bears, wolves and wild boars. They would grieve for a favourite dog or horse and make a grave for it.

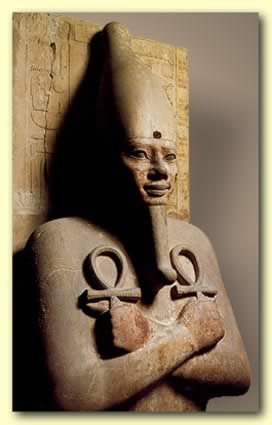

In many of the dolmens or tumuli such as Newgrange, are found scratched carvings similar to The Egyptian Sun Boat. Did the Celtic early beliefs come from Egypt? The archeologists and experts have all concluded this points strongly to an “Other World” doctrine or belief. Some even think the dolmens themselves were intended to represent a ship, taking the soul to a Far World guided by the God of Light - the sun. The ankh or Egyptian symbol of vitality and resurrection was sometimes scratched on dolmens.

It meant eternal life in ancient Egypt; I found one in a village church in Languedoc.

And like the Egyptians, the Celts believed the soul of the departed would live somewhere else in the Other World exactly as he had lived in this one; that’s why his possessions were buried with him. And he would come back to continue his first life. There’s even a record that a Celt would lend money on a promissory note for repayment in the next world, Valerius Maximus wrote in 30AD. However, it strikes me the Celts thought the Romans had no sense of humour!

By this time the Romans were recording a shift in what the Celts believed; it was not that the actual body would travel to other worlds and return, as the ancient Egyptians thought, but that the soul of the departed would reappear later in another body. There are Celtic tales of people recounting something that a dead person had told them; when friends and neighbours went to the place mentioned, all was as the previous life had known it but not the present one. The soul returning in a different body was a Pythagorean idea that the Romans dismissed, not understanding the concept; the only way a Roman got eternal life was if he was deified, as some of their emperors were.

The Celtic belief in the immortality of the soul did not include any idea of karma or moral retribution. The Celts saw the Other World as a pleasant place and had no concept of heaven or hell, eternal reward or eternal punishment. Full-stop. Personally, I am in total agreement with this, and discuss it in detail in my book.

The Celtic religion existed before the Druids did, the wise men of the tribes, who taught philosophy and natural sciences, and who settled disputes and legal matters. The Druids had seats of learning, especially in Ireland; Caesar described how people flocked to them. Soon after the Christians came, Ireland was covered in monasteries, such as Slane, where the basic belief in reincarnation of the soul remained, against the tenets of the Roman church which punished people with Heaven or Hell forever. It seems these monasteries were descended from Druid "mystery schools."

In Languedoc, south of the Aude river, Roman Christianity came around 750AD with Charlemagne; could it be that the many monasteries and abbeys he founded were built on the sites of Celtic or Druid holy places? Lagrasse for example claims to be founded by Charlemagne, but it was not, as the many Visigothic vestiges prove. And it is suspected that the cathedral at Alet-les-Bains was a “pagan” religious centre before Bera took it over in 813. (He did not build it; it was already there.)

Even under the Romans, and then the early Christians, the Celts worshipped heavenly bodies, the sun, moon and planets, but also rivers, trees, wells and mountains. This concept is coming back in spirituality today. I have a friend who used to tell me which mountains were sacred and which weren’t. (An ancient ancestor talking through her perhaps.)

In the 5th century the adoration of sacred trees, wells, springs and mountains by the people was denounced by the Roman church, in Arles. One had to worship God and no-one else. This disapproval by the Church has continued to the present day. But now people believe again that Holy Wells, such as the one at ND de Marceille, can cure diseases. And how many people visit the Holy healing water at Lourdes? Don’t forget, the Marian vision only appeared in the 19th century. The Roman Church is still fighting “paganism” by taking over the sacred places.

The Celts had no fear of death, unlike our societies today of people want to live forever. The Celts feared nothing, even though the earth were to split under them, and the skies to fall down on them. They did not even fear the waves, though they regarded them as hostile, and sometimes they would rush into them and fight with them and perish instead of retreating. One of their Gods fought the waves for seven days. This foolhardy bravery was legendary and partly due to their belief in the continued existence of a person after death.

The Celts went into battle naked; they were not afraid of death

The Celts went into battle naked; they were not afraid of death

For the Celts, religion was not something apart, that one thought of only when attending some sort of ceremony, but was bound up with everyday life in such a way it could not be separated. Religious deities were not merely concepts to be remembered from time to time, but were ever-present. The supernatural was the same as the natural, the divine the same as the mundane; the Other World or Far World was as real and tangible as the ever-present world.

Before the Roman influence, the Celts did not have temples, but they had nemetons, (sanctuaries), “Sacred groves” with trees and a natural water source or river. As well as religious ceremonies, these were great meeting places, for they did not have the division into natural and religious that we have today. The ritual gatherings were accompanied by lavish feasting and drinking, games and races and markets formed part of the event. They had shrines made of timber were offerings were left; later stone temples were built. The Romans would then have carved dedications - in Latin.

The first festival of the Celtic Year, Samain on the 1st November, was the day that the Other World became visible to mankind, the forces of the supernatural were let loose on the world, it was a time of great danger and spiritual vulnerability, charms were made to ward off evil spirits and a time when ancestors had to be honoured, we are told. This does not tie in with the idea that the Other World was as natural as this one; it seems that the Celtic religion had evolved under the influence of others, probably the Romans, for the two nations in Languedoc merged peacefully with each other over a period of around 300 years until they became the Gallo-Roman people.

But in the mountains of Occitania, if you know where to look, the ideas of the Celts are never far away.

Books used for reference;

Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race, T.W. Rolleston, George G. Harrap and Company, 1911.

Everyday life of the Pagan Celts by Anne Ross, Batsforth 1970

The Jesus Papers by Michael Baigent, Harper Collins, 2006

Inscrivez-vous au blog

Soyez prévenu par email des prochaines mises à jour

Rejoignez les 28 autres membres